Justice: A Caribbean Conversation

Chattel slavery is a thing of the past. It is also true that Abraham Lincoln’s 1863, Emancipation Proclamation did not erase slavery’s stain. Besides, slavery’s ugly legacy did not disappear with the Slavery Abolition Act that came into force in 1838 throughout the British Colonies.

While various entities have made acknowledgments and statements of regret for their predecessors’ roles in enslaving, exploiting and discriminating against people of African descent, reality dictates that an apology is just not enough. Between 1985 and 2009 apologies have come many quarters.

Pope John Paul II, head of the Catholic Church, apologized for slavery. Connecticut-based insurance giant Aetna said it had “deep regret” for selling slave insurance policies. The Anglican Church of England apologized for enslaving Blacks and taking profits from slavery.

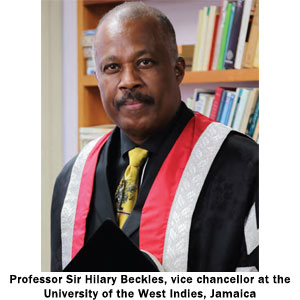

In 2009, the State of Connecticut passed a resolution apologizing for its role in slavery. And that same year, the United States Congress did likewise, adding that its admission of wrong is not to be the basis of future claims for reparations for the economic, social, psychological, and intergenerational damage slavery inflicted on Black populations. Professor Sir Hilary Beckles is a Barbadian historian and vice chancellor at the University of the West Indies, Jamaica. He is the chairman of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Reparations Commission and is leading a campaign to obtain reparatory justice for the nations of the English-speaking Caribbean. In his book “Britain’s Black Debt,” Beckles singles out the British government as the masterminds.

“They built the slavery system for taxation, revenue generation, profits, trade, finance, and they legislated it,” he said. Beckles strongly advocates that “it is Britain’s responsibility to assist its former colonies in repairing the damages slavery has caused.” But far from answering the demands for reparations, the government of Great Britain has not even apologized, only that it feels “deep sorrow” for the enslavement of Afro-Caribbean people. The English-speaking Caribbean islands have been independent for 40-50 years, and our leaders have done a remarkable job. The next phase of nation building, Beckles says, will bring economic hardships. Increasing diagnosis of hypertension and diabetes, high levels of illiteracy as seen now in some countries, unstable family structures as manifested by large numbers of single-parent homes will all strain national budgets.

These problems are the ugly side of slavery’s legacy that will hurt the region’s capacity for nation building well into the future, says Beckles, and these are some of the areas that reparations can fund. Georgetown University recently apologized and at the same time, unveiled a plan to provide reparations to African American descendants of the people they enslaved. In an address to African Americans, University President John J. Degoia told the audience, “the most appropriate ways for us to redress the participation of our predecessors in the institution of slavery is to address the manifestations of the legacy of slavery in our time.” Professor Beckles warns that “if Caribbean people relinquish their responsibility to demand reparatory justice for slavery, it will have dire implications not only for them but it will also have relevance for their children and the future of the region.” Obtaining reparations requires the peoples of the Caribbean and their supporters to stand united and vigorous in their demands for justice, because as Professor Beckles points out, “weak people don’t get reparations.” He cautions those who are against the idea, that reparation is not a handout.

“We are asking for a moral conversation, a legal conversation about justice.” Reparations will go to those nations that have an informed citizenry and those that have the belief that they deserve justice and that their children and grandchildren’s futures depend on it. Professor Beckles points to historical precedents for reparations. Nineteenth-century West Indian planters used the event of emancipation to obtain £20 million in reparations from Great Britain in return for the loss of their enslaved. France demanded and extorted millions of dollars in reparations from the treasuries of Haiti, its former slave colony, in exchange for Haitian independence. Europeans elites in both cases regarded themselves worthy of reparations.

The legal end of slavery in America and the British Colonies was welcomed by the enslaved. Since then, apologies have come from many quarters. In September 2016, a United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent said that the U.S. owes reparations to African Americans. But from the perspective of Professor Sir Hilary Beckles and those he represents in the Caribbean region, mere words cannot adequately address the lingering negative consequences that slavery has inflicted on English-speaking Caribbean societies, only reparatory justice can. Professor Beckles, vice chancellor at the University of the West Indies (UWI), will be the guest speaker at Central Connecticut State University (CCSU) Amistad Lecture on Tuesday, February 28. The theme of the lecture is “The Reparatory Justice Movement, 21st Century Enlightenment and the Legacy of the Amistad.”